Film review: A Compassionate Spy documentary deepens the historical discourse around Oppenheimer

Filmmaker Steve James tells the story of atomic physicist Ted Hall, who passed secrets to the Soviets

Re-enactments meet archival research in A Compassionate Spy.

A Compassionate Spy opens at VIFF Centre Vancity Theatre on August 4

THE NEW DOCUMENTARY A Compassionate Spy makes a perfect companion to Christopher Nolan’s summer blockbuster Oppenheimer—and will help you see it with fresh eyes.

Where one is a sweeping look at the race to build the atomic bomb, and its aftermath, the other zooms in on one character only briefly mentioned in Nolan’s epic effort—one whose actions changed the entire face of the Cold War.

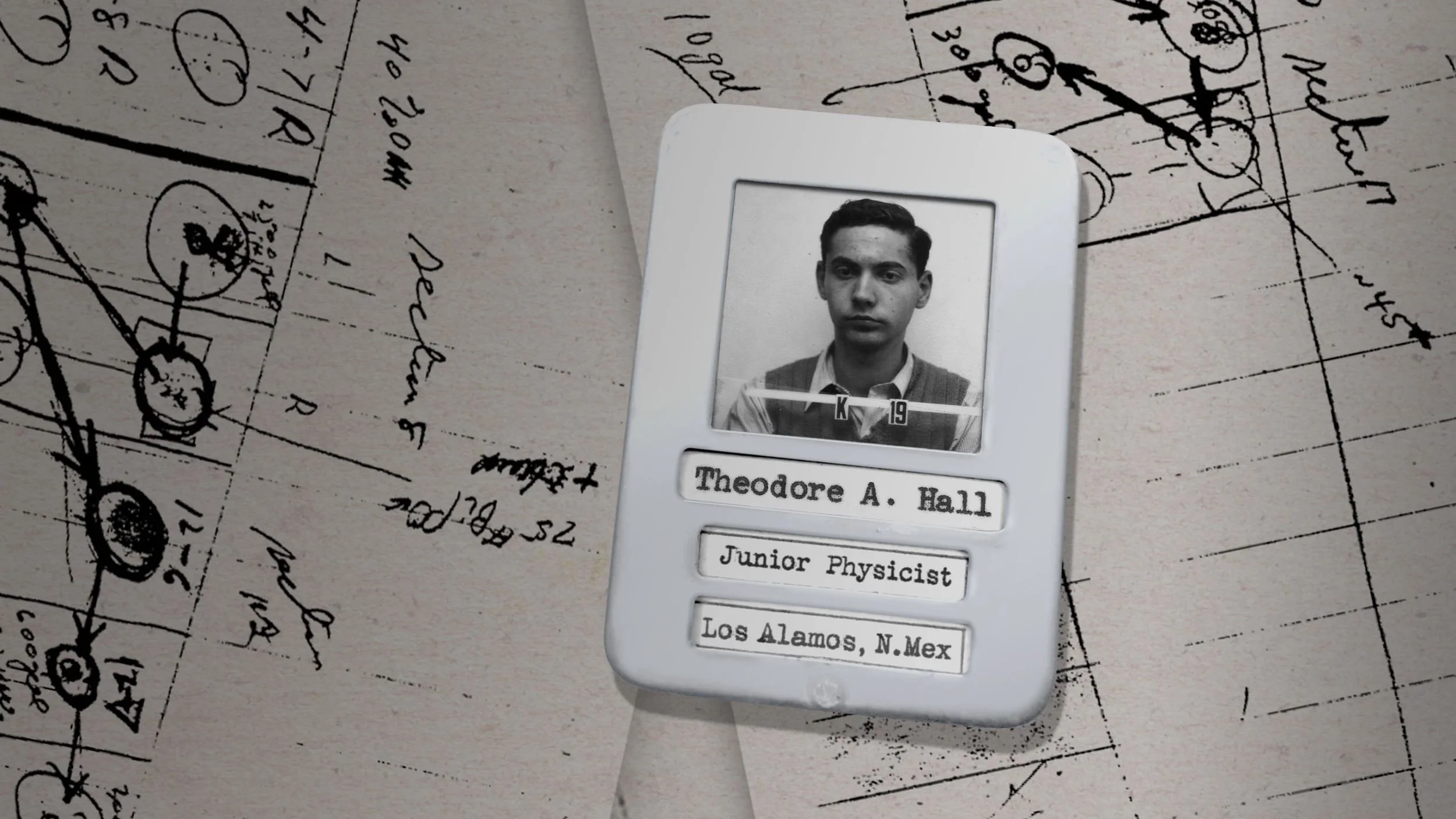

Hoop Dreams filmmaker Steve James profiles Ted Hall, who, at only 18, was a leading Harvard physicist recruited to the Manhattan Project. While helping to create the atomic bomb, he came to fear the effects that a U.S. monopoly on the weapon would have on global stability—and began to share secrets with the Soviets.

Through the eyes of his surviving nonagenarian wife Joan, we come to know Hall as an intellectual not unlike Oppenheimer. He was a classical music lover who would pass codes through Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Like the Nolan character, he’s also a bit of a heartthrob; says the spirited Joan, “Did I forget to say he was beautiful?” We learn about their early courtship at the University of Chicago, where they’d sprawl on the floor listening to Mahler (reproduced in James’s impressionistic re-enactments). And like Oppenheimer and his spouse, Hall and his wife were drawn to communist ideals—a fact James contextualizes with clips from America’s pro-Russian wartime propaganda (think Mission to Moscow).

Hall, seen in interviews, finally confessed in 1998, a year before his death, to having passed not just nuclear secrets but actual drafts of the implosion bomb to the Soviets. Still, he managed to evade any prosecution.

The intrigue here comes in the historical assertions. In Oppenheimer, Nolan only hints at the idea that Japan may have already been looking for ways to surrender before the bombs were dropped. James goes further, digging into the more progressive assertion that the Japanese were not even the true “target” of the bombing of civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki: it was the Soviet Union, and its rising threat under Stalin. The evidence shown here—including Truman’s increasingly exaggerated justifications in the months and years after the bombings—deepen and reframe a lot of what you witness in Oppenheimer.

By the end, the documentary shifts fully into an espionage thriller, the Halls evading the FBI and terrified of meeting the same fate as Julius and Ethel Rosenberg—whose own acts arguably pale next to the atomic physicist’s.

Many will find the film a little too “compassionate”, told as it is through a loving widow who proudly dubs Hall a “wunderkind spy”. Hall himself did express some regrets late in life—mostly to do with his major misread on Stalin.

To his credit, though, James reveals the complexity of the time and of the moral questions around Hall’s act, from the perspective of 21st-century global instability. Though it’s never addressed directly, there are moments of arrogance here—Hall describes exhilaration at achieving the bomb, echoing the flashes of hubris you see in Cillian Murphy’s Robert Oppenheimer. Pair the documentary with the bigger blockbuster, and you start to get a fuller picture of the era and its players—no matter how you ultimately judge them.