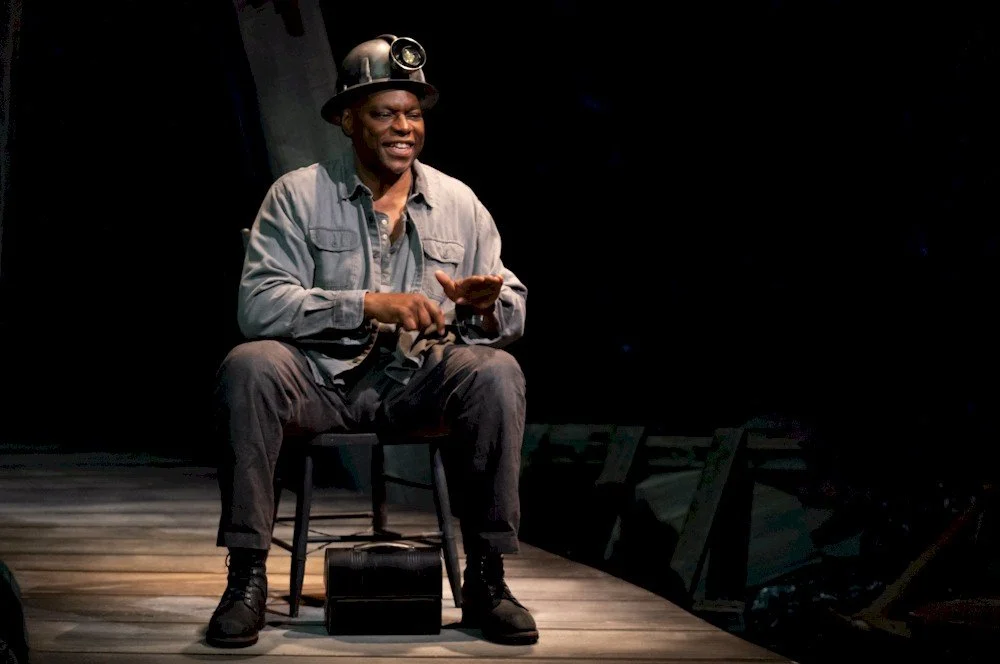

In Beneath Springhill: The Maurice Ruddick Story, Jeremiah Sparks finds joy in song

The solo show is based on true events of a 1958 mining disaster and the African-Canadian man known as the “singing miner”

Beneath Springhill: The Maurice Ruddick Story. Photo by Moonrider Productions

The Arts Club Theatre Company presents Beneath Springhill: The Maurice Ruddick Story from January 5 to February 4 at various Metro Vancouver venues

JEREMIAH SPARKS GREW UP singing in church on Sundays in small-town Nova Scotia. He became the venue’s organist at age 16, a position he held for more than two decades, while also acting as the director of the choir. So he comes naturally to his starring role in Beneath Springhill: The Maurice Ruddick Story, which was created by Beau Dixon and is being presented by the Arts Club Theatre Company.

Based on true events, the solo show tells the tale of the African-Canadian man also known as the “singing miner”. In 1958, 75 miners died after an underground seismic shock wave jolted the No. 2 mine in Springhill, Nova Scotia. Twelve men were rescued after spending six days trapped near the bottom of North America’s deepest coal mine, at more than 4,000 feet; another seven were rescued two days later, their plight captivating people all around the world. Throughout their horrific ordeal, they had little food, water, air, or hope—but they had song.

After the mine shaft caved in, Ruddick, who was born in 1912 in Joggins, Nova Scotia, helped keep his six fellow workers’ spirits up by singing and leading them in song and prayer. Later, he wrote a song about the experience called “Spring Hill Disaster”. Although the “miracle miners” garnered public attention far and wide, racism took away from Ruddick’s celebrity; he was the only Black person in the group. The father of 12, who was a descendent of slaves brought to the Maritimes by Loyalists in the late-18th century, died in 1988, 30 years after being named Canadian Citizen of the Year.

“It [This story] was a piece of Black history I didn’t know about,” Sparks says in an interview with Stir from his Toronto home. “My mother, I found out later, she knew all about it. I had never heard of this man and she had. It’s a great story about the resilience of the heart. I enjoyed that aspect reading the script. It’s just a great story. And it’s a Scotian story, and I’m from Nova Scotia.

“Once I got the role, I felt like it was made for me,” adds the actor, singer, and composer. “The different textures of the characters I need to portray is quite a stretch for me; it’s quite a thing to attack at the beginning. I’ve never done anything like that before but with the help of [director] Bobby Garcia, we were able to do this.”

The role calls for Sparks to play 10 different characters, including Ruddick’s wife and nine-year-old daughter, other miners, and a news reporter. Featuring music and lyrics by Rob Fortin and Susan Newman, the play (originally directed and developed by Linda Kash) is as relevant now as ever.

“It talks about race, but it’s definitely not just about race,” Sparks says. “It’s about strength and resilience of the heart. When people are together in the same catastrophe or the same disaster, no matter what colour you are, you need to work together to survive. That’s what comes across in this play.”

Sparks also works in commercials, films, and cartoons, with past theatre credits including Hosanna, Satchmo Suite, The Odyssey (Stratford, as actor and composer), Mother Courage, A Christmas Carol, and Oliver (National Arts Centre). He travelled to Uganda to perform the lead role in Cake, a play produced at the Biyimba International Arts Festival, and he has released two albums.

Theatre stands out for him because it’s one of the best ways to tell a story, something he has developed a knack for while raising his five daughters, ranging in age from 20 to 34. He has two step children and three grandchildren.

“I’ve always loved telling stories and listening to stories,” Sparks says. “That’s one of the things that strikes me a lot when it comes to theatre: people are there to tell a story the best way they know how with what they have. It’s different in film. In film, things are set up for you; there’s less to leave to the imagination. I love theatre because of what it does to the mind: what we can imagine is bigger than in film.”

Of course, the role of Ruddick also requires singing, and the style in Beneath Springhill goes well beyond belting out big numbers and the blues. “Sometimes I have to sing as if I can’t breathe,” Sparks explains. “I have to use different textures at different times. Sometimes it’s barely audible but still has to be somewhat real.

“I enjoy what singing does to the body,” he adds. “I love music. I have always loved music. When I’m coaching music and teaching music, I’m all about feel. I love the feeling that singing does to the body and the vibrations that are captured within yourself that blesses those around you—if you’re on pitch that is; otherwise it’s not such a blessing. I go to karaoke, and it’s a joy to watch people who can’t really sing lose themselves in a song, lose themselves in the joy. That’s what singing does.”