With J.E.H. MacDonald? A Tangled Garden, Vancouver Art Gallery lets viewer in on forgery detective work

Unusual exhibit shows the way microscopic paint analysis and art-historical expertise reveal donated sketches were not created by Group of Seven founder

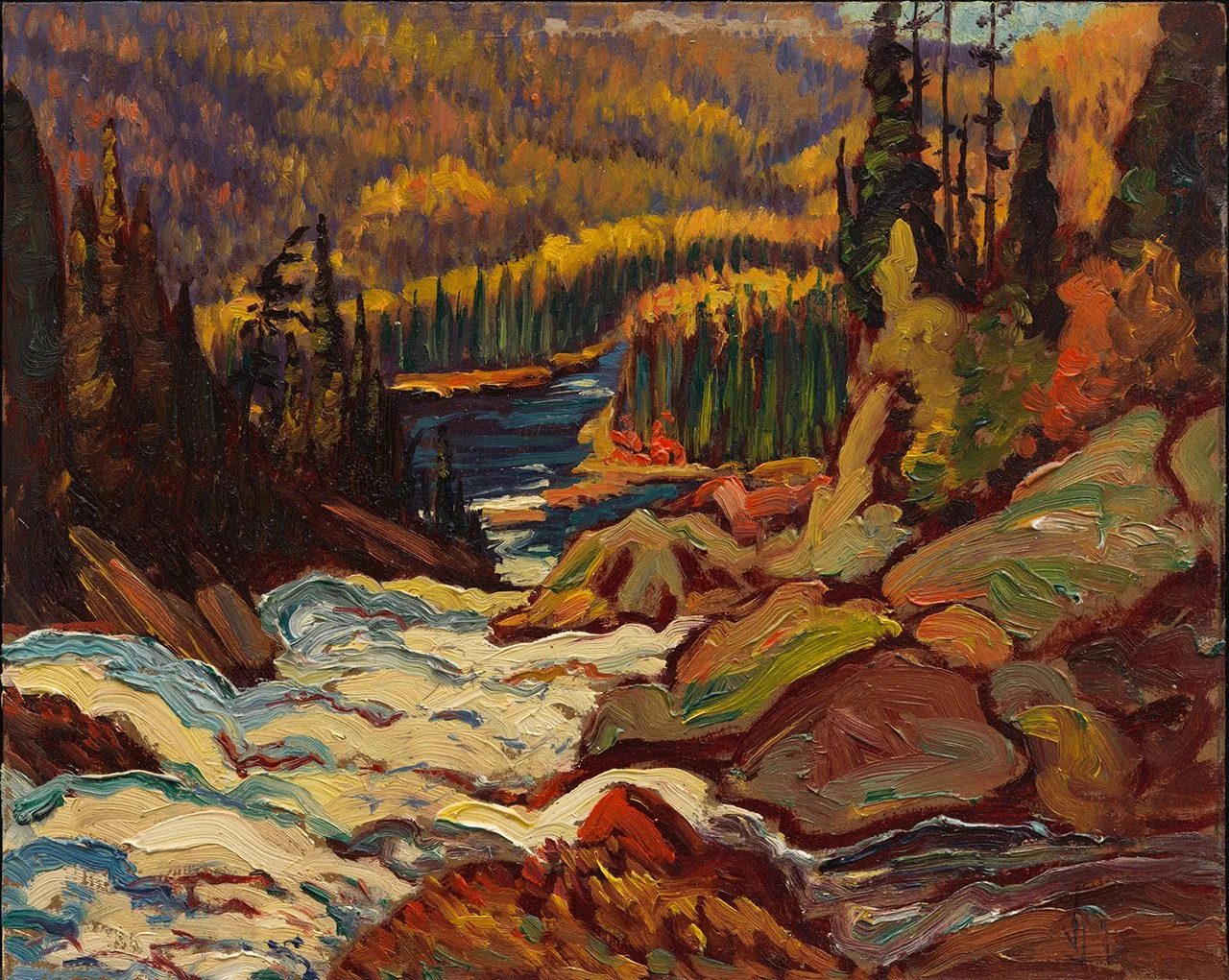

Unknown, Sketch after The Wild River, n.d., oil on paperboard, is missing the original riverbank in the bottom left of the image. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery

Vancouver Art Gallery presents J.E.H. MacDonald? A Tangled Garden to May 12, 2o24

IT CAME DOWN to the rutile titanium white and the phthalocyanine green pigments in the paint.

That’s just one of the eye-opening discoveries in a new exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery that acts as a full airing of a years-long investigation into the authenticity of 10 supposed J.E.H. MacDonald painted sketches. They had been donated to the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2015.

The gift of the Group of Seven member’s work had been a coup for the facility. But, as the show J.E.H. MacDonald? A Tangled Garden details, scientists at Ottawa’s Canadian Conservation Institute discovered pigments in the oil paints that did not exist before the artist’s death in 1932. As reported far and wide in the past week, they’re fakes. And now an unusual exhibition with the question mark in the title reveals how art historians, scientists, and other experts came to that conclusion.

“For this kind of process we like the facts to speak to us,” CCI conservation scientist Kate Helwig tells Stir. She trained as a chemist and works with a team of eight at the centre, which is part of the Department of Canadian Heritage. “We took microscopic samples of the paint with surgical tools and analyzed them.”

Curated by Richard Hill, the gallery’s Smith Jarislowsky Senior Curator of Canadian Art, the exhibition follows the chronology of the controversy around the paintings, from the initial press releases celebrating the donation to the subsequent analysis that goes on behind closed doors in the art world.

Video interviews with art historians and other experts interweave with displays tracing the stylistic analysis, forensic handwriting assessment, and other studies of the works that started in 2016. From the get-go, art historian Charles Hill (curator of Canadian Art at the National Gallery of Canada, heard on video in the show) sensed the palette was a bit off, and that the brushstrokes were a little more regular, with less variety and definition, than in MacDonald’s work.

The entry to the exhibit celebrates the VAG’s collection of verified oil-on-paperboard sketches by MacDonald and his Group of Seven colleagues—and emphasizes the value of these energized pre-works that were often painted in situ, be it on the banks of Lake Superior or deep into Algonquin Park. Midnight-green evergreens spike upward from autumn-mustard deciduous trees in MacDonald’s sketch Polars and Spruce, Algoma, from 1919-20, while a towering peak becomes a transcendent purply mass in the later Morning Light, Rocky Mountains (1931), both from the Vancouver Art Gallery collection. (MacDonald’s oil-on-paperboard painted sketches can easily fetch $100,000 to $200,000 and up at auction.)

There is even an interactive “Test Your Eye” section where viewers can guess whether a work is a real or fake MacDonald, and scan a QR code to see if they’re right. Further along, guests can examine damning inscription evidence—such as the fact that the oil-on-paperboard work Untitled (Batchawana Rapids) has a glaring error on the back, where a testament to its “authenticity” misspells MacDonald as “MacDnald.”

What makes the show more fascinating, though, is that it’s about a new transparency at the institution. After the initial donation, the gallery postponed a planned exhibition of the works to launch a study into their authenticity. CEO and executive director Anthony Kiendl did not head the VAG when the donation came in (that was Kathleen Bartels, now executive director and CEO of the Museum of Contemporary Art Toronto) but he says he decided almost immediately after arriving in 2020 that he wanted to organize a show around the discovery that the works were likely fakes. And here we are nine years later, with the exhibition finally opening to coincide with the release of the new book J.E.H. MacDonald Up Close: The Artist’s Materials and Techniques (Goose Lane Editions), authored by CCI’s Kate Helwig and Alison Douglas of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

Unknown, Sketch after The Wild River, n.d., oil on paperboard, is another work thrown into question in the exhibit. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery

“What's important is we’re transparent and we’re humans, and that we move on in an authentic way,” Kiendl explains. “The process of self-reflection is ongoing—it’s essential and one that each arts institution will go through.”

For curator Richard Hill, the exhibit is also a revealing look beyond the misconceptions of what he calls “the Antiques Roadshow Syndrome”—“when an expert looks at something and immediately starts saying what the history is. There’s a lot of research that goes into these things.”

Some of that research here offers deeper insights into the way the Group of Seven worked. Often, MacDonald and others would fuse elements from two separate landscapes. In the case of a forged sketch here for MacDonald’s painting The Elements, art historians know that for the final work, in the collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario, the artist mixed a churning cloudy sky from one location with a landscape from a Georgian Bay sketch. Therefore this supposed in situ sketch depicts a land-and-sky combination that never existed in real life, a fact that led artist historian Charles Hill to conclude it was adapted from the final painting. Similarly, in Sketch after Falls, Montreal River, where white water sloshes over reddish rocks, art-historic detective work uncovered the fact that MacDonald had removed a riverbank from the bottom left of the original sketch for his final painting—but it’s not here in this study supposedly painted at the site.

Looking at the exhibit’s wall-sized black-and-white portrait of MacDonald, sketching under a wind-bent poplar tree on Sturgeon Bay north of Parry Sound, one wonders what he might have thought of this commotion. Born in Durham, England in 1873 to Canadian parents, he studied art in Hamilton and Toronto before founding the Group of Seven, joining Tom Thomson and the others on their sketch trips to the great outdoors, where they’d paint before returning to their studios to turn those images into their more famous larger canvases. MacDonald also taught, running Toronto’s respected Ontario College of Art in later life.

As a longtime teacher, MacDonald might have appreciated the lessons learned in this exhibit opening nine decades after his death. And as attuned as he was to the unknowable forces of both nature and the art world, he probably would have appreciated the fact that no amount of science or handwriting analysis could answer all the questions surrounding these forgeries. At the gallery, Richard Hill admitted the team will probably never know who painted these 10 sketches once attributed to MacDonald, nor where exactly they came from. (They were reportedly sourced from the homes of Toronto art collectors; as for before that, Globe and Mail reporter Marsha Lederman, who dug extensively into the issue over the years, traced the purported provenance of the sketches back as far as being buried in an Ontario backyard.)

As Hill puts it: “There are mysteries within mysteries.”