Pictures and Promises exhibit takes a timely look at the lure of advertising

Art intersects with signage and consumer culture in show cocurated by the Capture Photography Festival and VAG

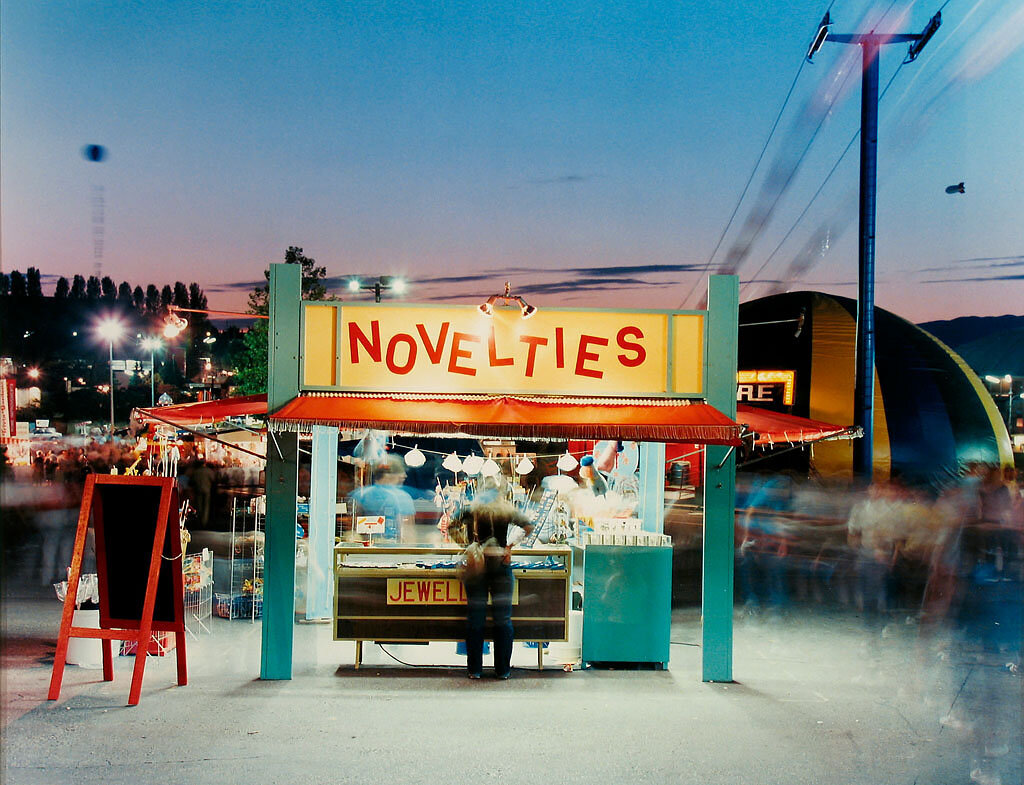

Lorraine Gilbert’s Untitled (from Vancouver-Montreal Night Works). Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Gift of the Artist

The Vancouver Art Gallery and the Capture Photography Festival present Pictures and Promises until September 26. See COVID-19 protocols here. Curators Grant Arnould and Emmy Lee Wall give a virtual curators’ talk April 12 at 5 pm.

A SPRAWLING, salon-style wall of photographs in the Vancouver Art Gallery’s new Pictures and Promises exhibit distills the way advertising has called out to us through the decades.

In Harry Callahan’s Chicago 1952, the succinct neon word “BEER” beckons, while, nearby, glowing signs and billboards battle for attention in Fred Herzog’s Vancouver’s Granville St., from 1969. Next to that, a carnival novelties stand lures customers against a pinky-blue sunset in a Lorraine Gilbert photo from the mid-’80s series “Vancouver-Montreal Night Works”.

Around the corner, Walker Evans’s Torn Movie Poster predates all of them, his metaphorical Depression-era 1931 photograph of a ripped movie advertisement showing a glamorous couple looking in terror at an unseen threat.

Fast-forward to 2021, when advertising is even more ubiquitous, blasting at us in a relentless stream from handheld devices that Evans never could have foreseen. And it’s in this context that the smart and accessible new Pictures and Promises photo exhibit, cocurated by the Capture Photography Festival’s Emmy Lee Wall and VAG’s Grant Arnould, raises timely questions about our consumer culture and the way ads shape our views of the world—and ourselves.

Walker Evans’ Torn Movie Poster. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Acquisition Fund

The show, which brings together lens-based work that draws on commercial culture, mass media, fashion, and advertising, is an apt foray for Capture into its first co-curated exhibit.

“I think one of the things that Capture offers is to get people to think about image culture and how images operate in society and how we’re all so affected by images,” Wall, the former VAG assistant curator who took the helm of Capture last year, tells Stir. “It’s just kind of getting that visual literacy—so for kids, adults, everybody to think about what they’re seeing, why they’re seeing it, and what that means.”

Ken Lum’s Steve. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Acquisition Fund

Drawing work entirely from the VAG’s photo-rich permanent collection, Wall and Arnould named the display after a groundbreaking exhibit curated by American artist Barbara Kruger in 1981 at New York City’s the Kitchen. Staged at a time when a new wave of artists was responding to a proliferation in advertising, it featured pieces by the likes of Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman, and Richard Prince. Kruger’s own 1985 piece, Untitled (We Will No Longer Be Seen and Not Heard) serves as the perfect entry piece to the VAG show. It blends red text panels and monochromatic imagery appropriated from advertising, challenging you to consider who the “We” in her title is—women? The marginalized?—and who controls mass-media messaging.

The ‘80s, and Vancouver’s contingent of photo-based artists from that era, make a strong showing in the VAG exhibit. Vikky Alexander’s Obsession hails from 1983, when the longtime-Vancouverite and now Montreal-based artist was living in New York. It features 10 cropped black-and-white images of ubiquitous ‘80s supermodel Christie Brinkley overlayed in brash yellow-tinted Plexiglas that reflects our own image as we stare at her.

Vikky Alexander’s Obsession (detail). Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Gift of the Artist

“Think about the saturation of her imagery in American culture,” comments Wall. “Think that those 10 images would have been disseminated to hundreds of thousands of households through magazines.

“Also, historically, a photograph is thought of as sort of capturing one single moment in time, but what’s interesting in looking at a work like Obsession is that you really see that there’s this crazy proliferation and repetition of that image—and thinking about how that image operates in society in a broader context is really important.”

It’s fun to turn from those repeated images to the colossal stack of breakfast cereal in Roy Arden’s Wal-Mart (Apple Jacks) from 1996. Here the endless rows of bright-green boxes, emblazoned with a sales sign and set against a mass of plastic Halloween trinkets and candy displays, speak to a different kind of proliferation and consumption.

Elsewhere, Ken Lum’s 1986 work Steve brings together photography and the language of commerce in an entirely separate way. It’s Sears portrait meets commercial signage, as Lum’s subject smiles out from a mall-kiosk-style shot, his name blasting above his head like a brand logo.

O Zhang’s We are all the Future of the Earth. Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Gift of the Artist

The show ties in more recent work from around the world, most memorably Chinese artist O Zhang’s large-scale “The World is Yours (But Also Ours)” series. Shot in 2008 on the eve of the Beijing Summer Olympics, they picture teens in front of the capital’s landmarks, in T-shirts whose English slogans don’t quite make sense (one girl’s reads “It’s a Vegas show with the honesty professional” and she stands in front of the Olympic rings). Beneath them, in Chinese letters, are slogans, some Maoist.

“It’s this sort of perfect metaphor for how there's this longing in Chinese culture for a better life in the West—or the idea that Western culture is more advanced, like it’s sort of the Promised Land,” says Wall. “The idea of the T-shirts is that, although you might want to adopt Western ideals or products, that translation doesn't always fit in a different context.”

The brilliance of Pictures and Promise is that the disconnect and longing that O Zhang expresses here can connect so directly to the aspiration of Ken Lum's Steve or the irony of Walker Evans’ Depression-era movie poster--even though they were shot generations and continents apart. The power of persuasion is omnipresent, but the show helps us examine who holds that power, and over whom. And whether the promise is worth buying into.