Vancouver Art Gallery's revelatory Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Moment opens rich world of unsung talent

Many new names to discover in expansive exhibit of early-20th-century work that offsets the all-male Group of Seven’s centenary

Prudence Heward’s At the Theatre, 1928, oil on canvas, The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts Purchase, Horsley and Annie Townsend Bequest, Photo by MMFA, Christine Guest

Prudence Heward’s Sisters of Rural Quebec, 1930, oil on canvas, Art Gallery of Windsor, Gift of the Willistead Art Gallery of Windsor Women’s Committee, 1962

Vancouver Art Gallery presents Uninvited until January 8, 2023

THE WOMAN IN a flapper-era bob is definitely not the classic swimsuit pinup you might have seen tacked to the wall of an old 1930s garage.

Muscular and athletic, she sits, shoulders hunched, bathing suit sagging, legs awkwardly bent open on shadowy rocks. But it’s the gaze that most gets you in the large-scale, startling The Bather, a 1930 painting by Montreal’s Prudence Heward: rather than looking away demurely or seductively meeting the viewer’s eyes, she stares intently off into the distance, as inscrutable as Mona Lisa.

The figure sits in stark contrast to the bathers of painting over the last few centuries of art history, in all their idealized femininity. And she probably could only have been captured in this way by a woman.

“Her body is anything but erotic; she’s as hard as Teflon,” comments McMichael Canadian Art Collection chief curator Sarah Milroy.

Next to The Bather on a wall in the Vancouver Art Gallery’s major new Uninvited: Canadian Women Artists in the Modern Moment is Heward’s remarkable nude Girl Under a Tree, from 1931—labelled “one of the most eccentric nudes in the history of Canadian art”. Equally hard and sinewy, the woman here bends at an awkward angle at the base of a tree, her eyes looking off in an impenetrable mix of what might be anger and anxiety.

On a tour of the big new summer show at the VAG, Milroy reveals that the richly painted oil on canvas once hung over Heward’s own bed—and that the artist, well trained in the traditions of art, was purposely subverting the classic depictions of women here, too.

“This is really a provocation of the nude as supine, available, and confectionary,” Milroy comments.

Heward is just one of the many riveting discoveries at Uninvited, a monumental survey of more than 200 works of art by a lost generation of painters, photographers, weavers, sculptors, and others. Focusing on the period from 1920 to 1940, the exhibition was painstakingly organized by Ontario’s McMichael Canadian Art Collection as a counterpoint to the centenary of the all-male Group of Seven—who may have supported female artists like Emily Carr (who also takes a central role here) but never formally invited any into their boys’ club.

As she and her team worked on the project, Milroy says, “We said, ‘How can it be that this show hasn’t happened before?’ The underfunding and under-resourcing systemically over 100 years is nothing less than shocking.

“We decided out of the gates that we were going to fund this to the hilt,” she adds. “This is it: we’re building a battering ram with an exhibition that will make it irrefutable that we need to look at Canadian art in a different way.”

That echoes the fact that these accomplished women of the early 20th century also looked at the world in a different way. While celebrated male painters like Tom Thomson and Lawren Harris were hiking into Algonquin backwoods to pay tribute to rocks and pines, many of the women here were more interested in the human experience and psychology, industrialization, and urbanization. The portraits in the exhibit, as Milroy puts it, are often “deeply psychologically penetrating”. Often they capture the dramatic changes of their eras, and the shifting female roles and freedoms; another striking Heward work pictures two Jazz Age women enjoying themselves out alone at the theatre.

As broad and diverse as the exhibit is, often juxtaposing the work of settler women with the baskets, beadwork, and other creations by Indigenous women from the same era, it’s a compellingly curated, room-to-room experience. Each space tells a vivid, focused story, usually based around one or two artists and a single geographic region of the country.

“We really wanted to avoid the chocolate-box effect,” Milroy says, “so there are little mini exhibits for each artist….You can feel the distinct personalities.”

Suzanne Duquet’s Group, 1941, oil on canvas, Collection of the Musée national des beaux arts du Québec, Gift of the Artist, Photo by MNBAQ, Jean-Guy Kerouac, © Estate of the Artist

Standouts include the first hall, not just for Heward’s enigmatic portraits of assured women, but compelling works by her Montreal counterparts. Don’t miss Regina Seiden Goldberg’s A Pierrette, from 1925, in which the painter reimagines classical painting’s sad clown as a sassy, 1930s-modern woman. Then there’s Suzanne Duquet’s strange and intense masterwork Group, picturing the artist and her three scowling sisters in a claustrophobic domestic scene—Duquet, in her paint smock at an easel, at odds with her siblings’ feminine dresses and painted nails.

In a gallery space devoted to Northern Ontario, Bess Harris’s entrancing Day’s End, a depiction of the silver-mining town Cobalt, captures the humanity of what must have been a rough remote outpost: a lone coat hangs jauntily on a laundry line by one of the slanted worker houses, illuminated by an expressive pink-hued sunset. Yvonne McKague Housser depicts miners roaming a village of ice-cream-hued clapboard houses looking out at a Harris-esque sky and waterscape in Rossport, Lake Superior, from 1930. Both artists’ use of light is mesmerizing.

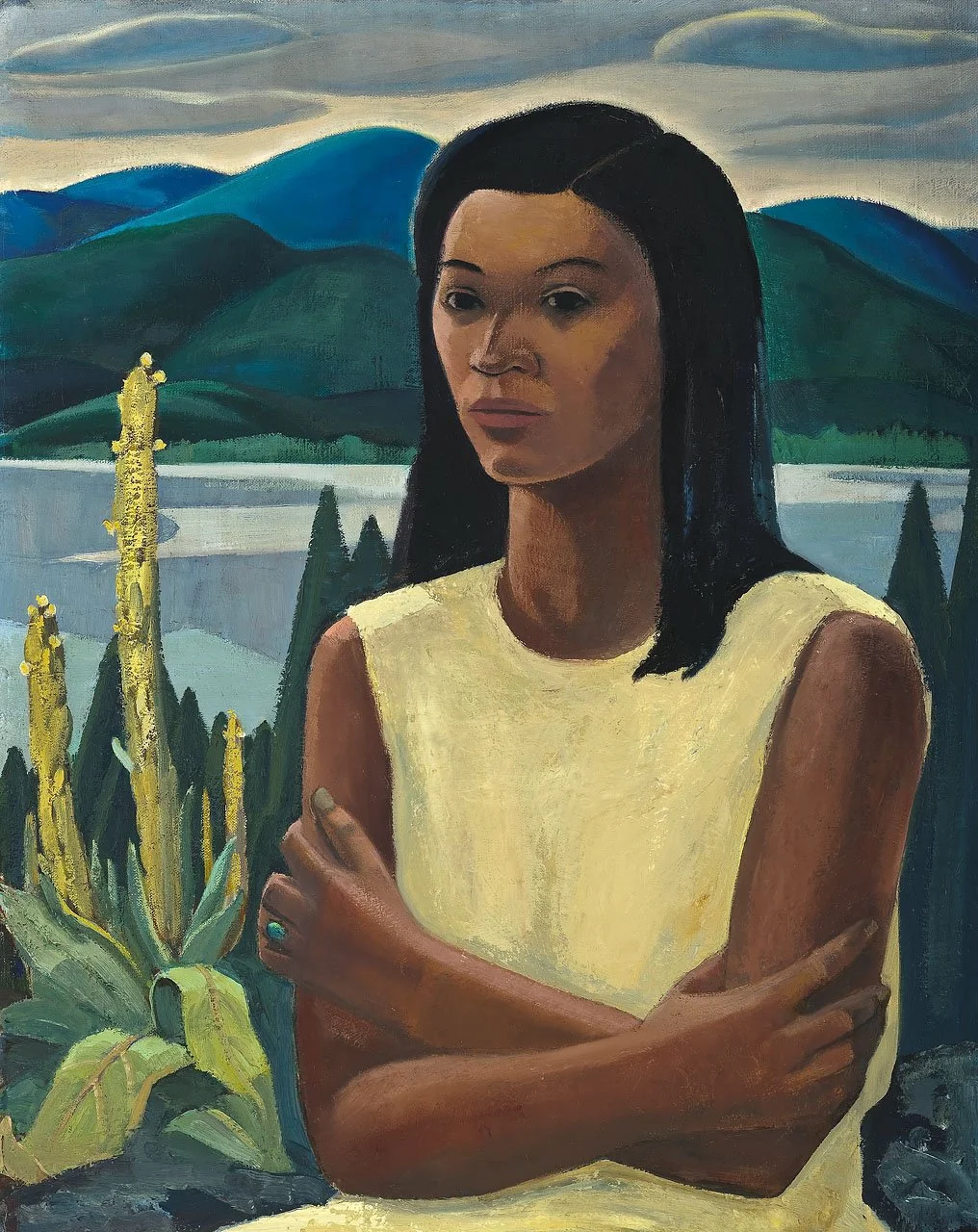

One of the most remarkable pieces here, though, is Housser’s Marguerite Pilot of Deep River, another of this exhibit’s stirring portraits, this time of an Indigenous woman who seems to express a mix of unease, agency, and remove—her crossed arms, as Milroy points out, forming a barrier to us fully knowing her.

A world away are the works from the Arctic and Nunavut, featuring Winifred Petchy Marsh’s subtle, detailed watercolours from the years she spent living in the Far North as the wife of an Anglican missionary. One, depicting a Padlirmiut woman’s atigi (or inner coat) is juxtaposed with a real, intricately beaded version of the same piece of apparel, by Attatsiaq.

Yvonne McKague Housser’s Marguerite Pilot of Deep River (Girl with Mulleins), c. 1936–40, oil on canvas, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Gift of the Founders, Robert and Signe McMichael, © Estate of Yvonne McKague Housser

Winifred Petchey Marsh’s Padlirmiut Woman’s Atigi or Inner Coat (Front View), 1933–34, watercolour on paper, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Gift of the National Chapter of the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, 1977, © Estate of Winifred Petchey Marsh

Other showstopping works include Pegi Nicol MacLeod’s The Slough, a radical and deeply haunting self-portrait, in which the artist’s own abstracted, agonized face melts into the spiralling stems and blooms of a cyclamen plant; photographer Margaret Watkins’s delicate, modestly scaled domestic still-lifes of tin-pan lids, soap dishes, and tea towels; and Vera Weatherbie’s passionate portrait of her lover, Group of Seven member F.H. Varley, as an almost spiritual, light-ray-emitting force.

The show culminates in a gallery space celebrating Emily Carr, the one woman in this exhibit who is truly well-known. Works like the wistfully expressive Logger’s Culls, depicting towering firs around a clearcut, are hung alongside some moodily stunning oils of BC landscapes by Montreal’s Anne Savage. Through the centre of the room sits an impressive collection of Coast Salish baskets—another artform, perfected by women, that was inspired directly by BC’s nature.

Aside from Carr’s dramatic works, however, it can’t be stressed enough: most of these artists would have disappeared into history had it not been for the dogged detective work of the Uninvited team. Milroy relates that many of the paintings shown here were sitting in descendants’ homes or attics, and so quite literally would have been lost without preservation.

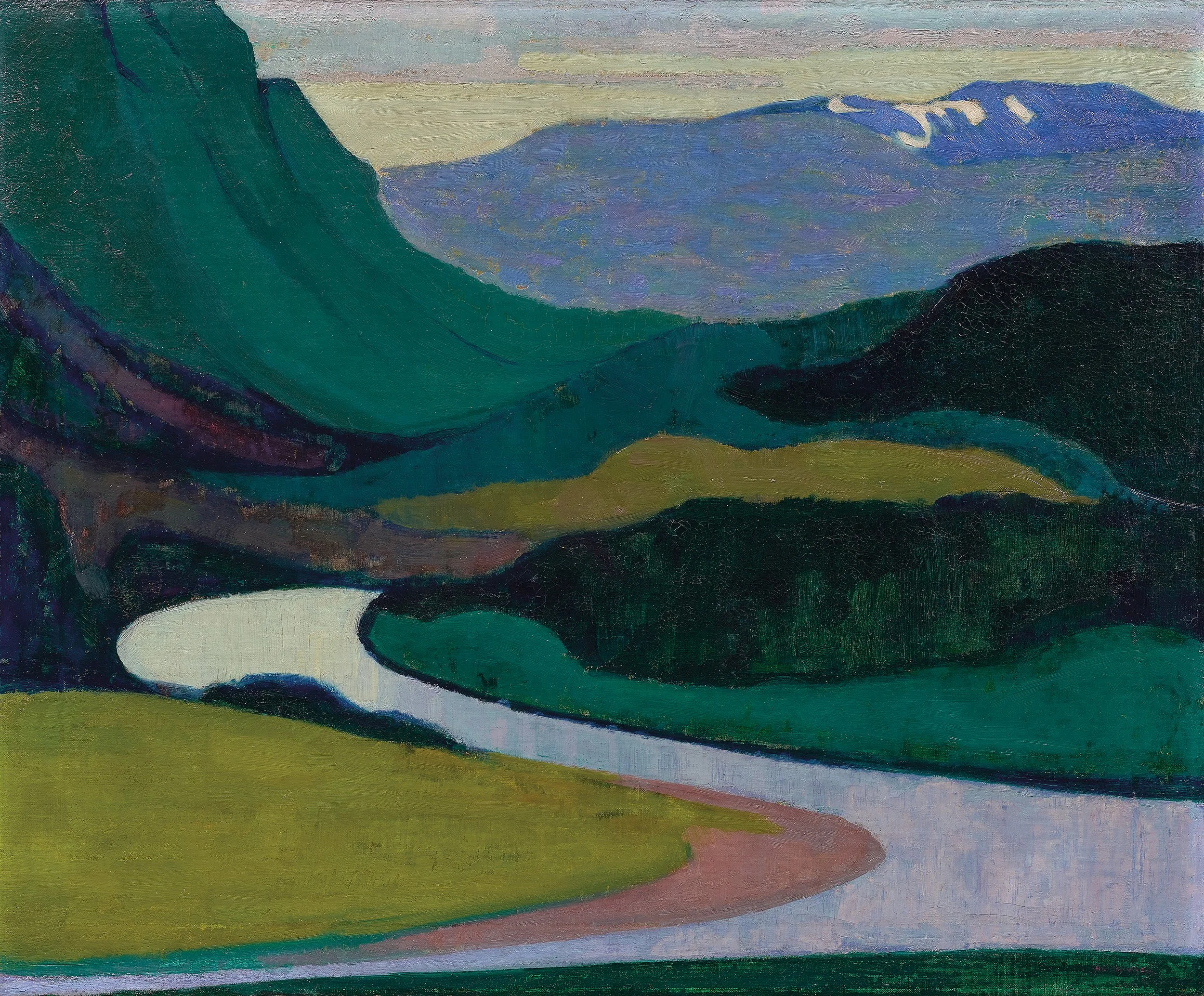

These unburied treasures include many stunningly expressive landscapes that could stand proudly beside anything by the Group of Seven.

But the portraiture is ultimately the biggest draw amid this astonishing "battering ram" of an exhibit: like The Bather, these complex painted female figures are people you yearn to get to know. Just like the artists themselves. Better late than never.

Anne Savage, Temlaham, Upper Skeena River, 1927, oil on canvas, Private Collection, © Estate of Anne D. Savage