Film review: Vortex's radical act of cinema adds up to a devastating look at mortality

Using split screens and extended takes, auteur Gaspar Noé takes viewers on an uncompromising trip to an elderly French couple’s agonizing end

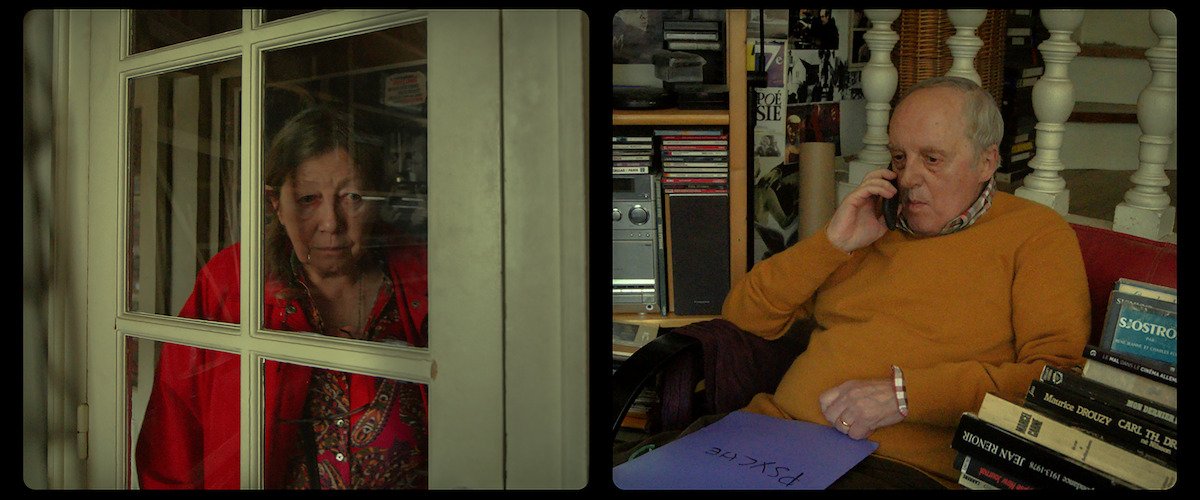

Depicted in split screen, a wife and a husband lead increasingly separate lives in the same apartment.

Vancouver International Film Festival presents Vortex from May 20 to June 2

AS UNLIKELY AS it sounds, one of the most radical acts of filmmaking this year centres around two octogenarians slowly shuffling off this mortal coil.

Argentinian-born, France-based auteur Gaspar Noé (Lux Aeterna, Enter the Void, both screening at VIFF Centre this month) has always pushed boundaries. But nothing prepares us for Vortex, a film that’s thrillingly uncompromising in its take on decline and death.

In his signature unconventional opening credits, the director dedicates the film “to all those whose brains will decompose before their hearts.” Take that as an early warning.

Noé makes inventive use of a split screen and extended takes to show us how an aging couple (played by Françoise LeBrun and filmmaker Dario Argento) have grown apart—and yet are inextricably bound. For long, uninterrupted sequences, we might watch the unnamed husband blithely sorting through papers in his study, making phone calls, and writing notes, as his wife wanders disoriented in their labyrinthian, book-stuffed Paris apartment. In one harrowing sequence, we see her head out alone for groceries, only to get lost, and increasingly panic-stricken, in the back corner of a hardware store’s paint section. Her husband, on the other side of the split screen, is phoning shopkeepers in an attempt to track her down.

Such scenes thrust us into a painfully untenable situation—one repeated the world over, as elderly husbands or wives realize too late, or deny for too long, how much their partner has slipped. And it never ends well.

Noé creates a subtle tenderness between these two people sharing a cramped cage, and he also builds almost unbearable tension as the woman, unsupervised, mixes her pills together, or lights the gas stove. We want to look away or intervene, but can’t.

Slowly, stealthily, the director metes out information about who this couple might have been in a previous life—her a psychiatrist, him a film critic. LeBrun and Argento both give the film a documentary-like authenticity. LeBrun’s character has lost her ability to string long sentences together, but the veteran actor conveys worlds of emotion in a look—at one moment, she wakes up in bed and it’s instantly clear that she has no idea where she is. And there are depths of despair in the few whispered words she can summon: “Take me home” or “I’m scared”. Horror auteur Argento is a perfect combination of erudite and petulant, strong and frail.

Eventually, their son Stéphane (Alex Lutz) and his own small child Kiki bring new complexity to an already difficult situation. Stéphane is a recovering drug addict indebted to his parents, but ill-equipped to care for them in the way they need. It’s the Anna Karenina principle at work: an unhappy family that’s unhappy in its own way, complicated by the fact that aging and illness are forcing its members into uneasy codependence.

In one poignant scene, Stéphane’s little boy bangs a dinky car on a desk, causing his grandmother to weep and he stares in bewilderment. Even a child can’t comfort her.

Noé pushes much further, unrelenting yet empathetic in the indignities he makes us witness. But as intense as the film is to watch—let’s not pretend this is pleasant—its ideas are profound. At the press screening, viewers sat awe-stricken, lost in thought processing the final moments.

Vortex’s deepest and most unsettling themes circle around the things we acquire. The husband doesn’t want to move with his wife into a care home because chunks of his whole life—his movie posters, his rare books, his photographs—are all here. And because we’ve been so immersed in this intimate space, his desire to hold on to what comforts and reminds him of what he’s achieved is completely understandable. “I don’t throw away my past,” he asserts.

But as the lights begin to fade, Noé reminds us, unsparingly, in his final, startling images, that all that we collect, create, and cherish is as ephemeral as life itself. It’s poignant and pitiless—a lot like this astounding and deeply moving act of filmmaking.