Black photographers capture and celebrate Black life in As We Rise

The new exhibition, subtitled Photography from the Black Atlantic, is drawn from Black Toronto-based art collector and dentist Kenneth Montague’s vast Wedge Collection

Texas Isaiah, My Name Is My Name I, 2016. © Texas Isaiah. Photo from As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (Aperture, 2021)

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic is at The Polygon Gallery until May 14

TORONTO-BASED DENTIST and art collector Kenneth Montague’s parents came to Canada from the Caribbean in the early 1950s, the Jamaican couple calling Windsor, Ontario home. His late mother worked as a dietitian, his late father as a teacher. The latter had a saying that became the family motto: “Lifting as we rise”. A new photo exhibition organized by Aperture now on at The Polygon Gallery draws from the phrase. As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic features a vast selection of images from Wedge Collection, Canada’s largest privately owned collection dedicated to African diasporic culture and contemporary Black life. It belongs to Montague, whose parents fostered a love of the arts in him from an early age and who, like his mom and dad, believes deeply in lifting others up.

“My father, who passed away in 2018, was a very sage guy who rose up with a lot of obstacles,” Montague says in a phone interview with Stir. “They came as the second Jamaican family to a city of over 100,000 in suburban Ontario….He loved his job as a teacher, and that family motto came from this idea that as we do well, we should pull up others in our community.

“Even as a child, I was exposed to public art galleries, and I think that early exposure to galleries made me realize, even as a 10-year-old, that I wanted to have a longer time with the artwork than just seeing it on the walls of a gallery or in a magazine,” he says. “I realized that I wanted to tell stories and bring marginalized or underknown artists into public consciousness. I wanted to bring young artists into the fold alongside known artists, and I started collecting.”

The Wedge Collection grew out of Sunday-afternoon salons Montague would host in the mid 1990s in his industrial-area loft apartment, the name a nod to the shape of its high-ceilinged hallway. His early focus was on emerging Black artists from Toronto. At the first event, close to 300 people showed up, and eight of 10 photographs were sold. “I just realized, ‘I’ve got a gallery on my hands,’” he recalls.

From there, Montague began doing exhibitions at public venues and founded Wedge Curatorial Projects. The non-profit arts organization supports emerging Black artists through public showings, lectures, and programs, to “wedge” those up-and-coming talents into the mainstream art world.

Montague’s collection now boasts more than 400 original works by artists from Canada, the United States, and throughout the diaspora. It also consists of an extensive catalogue of books, art journals, newspapers, and magazines and lends works to international traveling exhibitions. As his collection grew, so did interest in work by Black artists on a broader scale, albeit slowly.

“There haven’t been enough avenues and platforms for Black Canadian artists,” Montague says. “It’s been a very recent phenomenon that places like Vancouver Art Gallery or the AGO [Art Gallery of Ontario], these long-standing institutions, are finally beginning to collect work and open up the door and change the programming so that it’s a regular rotation where you see Black artists. It’s changed a lot in the last few years, but that was really not the case in my life. I’m in my late 50s, and it was something I just had to do myself. My interest in Black artists and how much enrichment it’s been in my life to be a collector… I wanted to share that with other people. So it became a kind of lifestyle, a mandate, a personal mission.”

As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic features some 100 works from the Wedge Collection, with Black subjects depicted by Black photographers. Curated by The Polygon Gallery’s curator Elliott Ramsey, the exhibition is the touring accompaniment to Aperture’s recently published book of the same name. As We Rise first opened at the University of Toronto’s Art Museum in the fall of 2022 and will travel to the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts later this year. It is also part of Vancouver’s 2023 Capture Photography Festival (April 1 to 30).

Anique Jordan, 94 Chestnut at the Crossroads (series of four photographs) 2016. © Anique Jordan. Photo from As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (Aperture, 2021)

Spanning nearly a century of photography, with images from the early 1930s to the 2020s, As We Rise features excerpts from the book emblazoned on the gallery walls. It has themes of identity, community, and power.

“The work in this collection is championing the careers of Black artists and also looking at representations of Black lives and Black experiences in visual arts,” Ramsey said in a media tour of As We Rise. “By looking at Black photographers capturing and commemorating and celebrating Black life and Black experience, we also tap into a really important moment in photographic history broadly. As you had the African independence movements on one side of the Atlantic, you also had, of course, the civil-rights movement happening in the United States on the other side of the Atlantic. And in these same decades, the ’50s and ’60s, you also have the camera becoming a more prolific tool, something that is becoming more accessible that people are using both in imaginative ways as well as documentary ways.

“You have these artists like Gordon Parks and Seydou Keïta who have really laid the groundwork for how photography—street photography, social and documentary portraiture—will be developed in subsequent years by artists all over the world,” Ramsey says. “And these paired moments of independence and civil rights with the rise of the camera have created this really rich visual legacy.”

Among the dozens of other artists featured in As We Rise is Deanna Bowen. The Toronto-based interdisciplinary artist, known for her auto-ethnographic practice, is seen in 2010’s sum of the parts: what can be named (a clip from a high-definition video) reading from the record of her family history, which she has traced back to slavery. In I Am Not Tragically Colored (after Zora Neale Hurston), a series of digital prints from 2013-14, Erika DeFreitas depicts herself pressing a plate of plexiglass against her mouth as she reads the line drawn from the African-American author’s writings. Anique Jordan’s 2016 94 Chestnut at the Crossroads (series of four photographs) shows a woman in mourning clothes lamenting the site of a Black church that was shuttered, expropriated, and destroyed in Toronto.

There is a section dedicated to Black bodies at rest. “I’ve often noticed how in media images we often see Black people playing sports, marching, fighting, dancing or performing or whatever it is; we just so seldom see images of rest,” Ramsey says. “And yet these Black visual artists work prolifically in this theme, and so I wanted to create a moment that really honours that.” An example is Je suis le cactus de Siberie by Malian artist Mohamed Camara, who splits his time between Bamako and Paris, from the 2006 Certain Matins series. The inkjet print shows a young Black man standing in swim trunks surrounded by snow, vacationing in the Swiss Alps. Jamaica’s Radcliffe Roye captures locals on certain beaches—though not the especially beautiful ones designated for tourists only. Texas Isaiah, one of the first trans photographers to photograph a Vogue cover, is featured, with My Name is My Name I featuring a nude individual sitting on a wooden floor, head down, under a large arching plant with sunlight flooding the floor. Hank Willis Thomas’s 2002 Jermaine & Logan captures two Black men at a friend’s funeral, one with tears rolling down his cheeks, capturing a vulnerability that’s counter to stereotypes of Black masculinity.

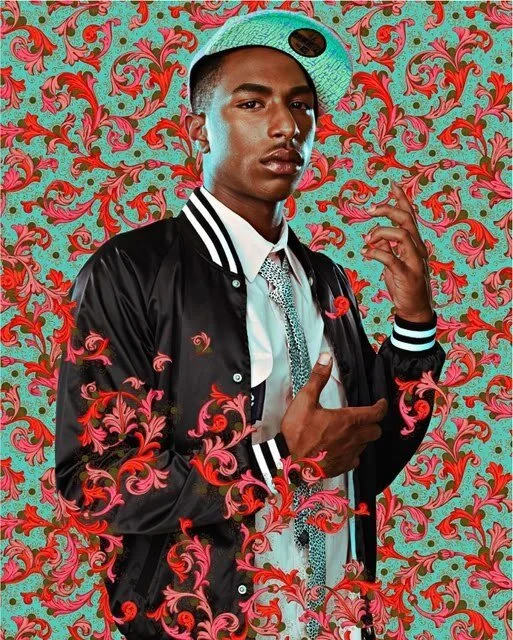

Kehinde Wiley, After Sir Joshua Reynolds’ “Portrait of Doctor Samuel Johnson”, 2009. © Kehinde Wiley. Photo from As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (Aperture, 2021)

There are images of Black people taking care of each other; photos that could easily fit into family albums; and images of forced and willful migration.

Pre-eminent Malian photographer Malik Sidibé’s 1963 Nuit de Noel (Christmas Eve), a silver-gelatin print, shows a couple dancing, forehead to forehead, an example of the way the artist captured Mali transforming socially into a free nation.

Malian photographer Seydou Keïta’s Keita, 2 babies, is an irresistible image of a set of wide-eyed twins that digs much deeper than the tots’ darlingness. Twins are significant in Yoruba culture, and the artist (who only gained wide recognition later in life) dressed subjects in elegant or fanciful costumes, as he captured Malian society in transition.

Featured artist Oumar Ly took to the streets to capture life in a newly liberated Senegal. “People wouldn't have necessarily felt welcome in a photo studio,” Ramsey says. “When you think about people who are living in a colonized situation, they’re not the ones taking the pictures; the colonizers are photographing them. So he created these studio backdrops. And you can actually see his studio assistant holding them up behind the people in every photograph, which I think is super incredible and scrappy and endearing. And these are such beautiful images capturing what life looks like in a way where the subjects are feeling seen and feeling safe and are very manifestly different from the kind of colonial photography that we would have seen prior. Just before this era, the imagery might be similar, but there's just a very different tone to them.”

Dawit L. Petros, Hadenbes, 2005. From As We Rise: Photography from the Black Atlantic (Aperture, 2021) Courtesy of the artist/Bradley Ertaskiran

James Van Der Zee’s Couple in Racoon Coats shows a 1932 pair “living their best lives in the Harlem Renaissance”, Ramsey says. The silver-gelatin print by the Harlem chronicler is the earliest work in the exhibition and the first photo that Montague collected. “This started it off, and it was this image of a kind of uplift of Black people succeeding and thriving,” Ramsey says.

Vancouver’s Stan Douglas is the lone Vancouver artist featured in the show. Malabar People: Dancer, 1951 is a 2011 chromogenic print from a suite of portraits of staff and patrons of a fictional nightclub in Hogan’s Alley during the era of train travel, when Vancouver’s night life was electric.

As We Rise also features works by American photographer Jamel Shabazz, who documented hip-hop coming into the mainstream; Dawit L. Petros, an Eritrean-born artist who now splits his time between Montreal and Chicago; and Toronto’s Tayo Yannick Anton, who focuses on queer people of colour and the decolonization of cultural events; among many others.

Kehinde Wiley’s 2009 After Sir Joshua Reynolds’ “Portrait of Doctor Samuel Johnson” (an archival inkjet print on Hannimule fine art paper) is a strong illustration of one of As We Rise’s key themes. The artist creates portraits with ornate backgrounds, elements of which sometimes flow atop or weave around his subjects; his works confront politics of race and power in art. This particular image is a reinterpretation of a historical painting in which the subject, a Black youth in street wear, mimics the gesture of a doctor holding a baby.