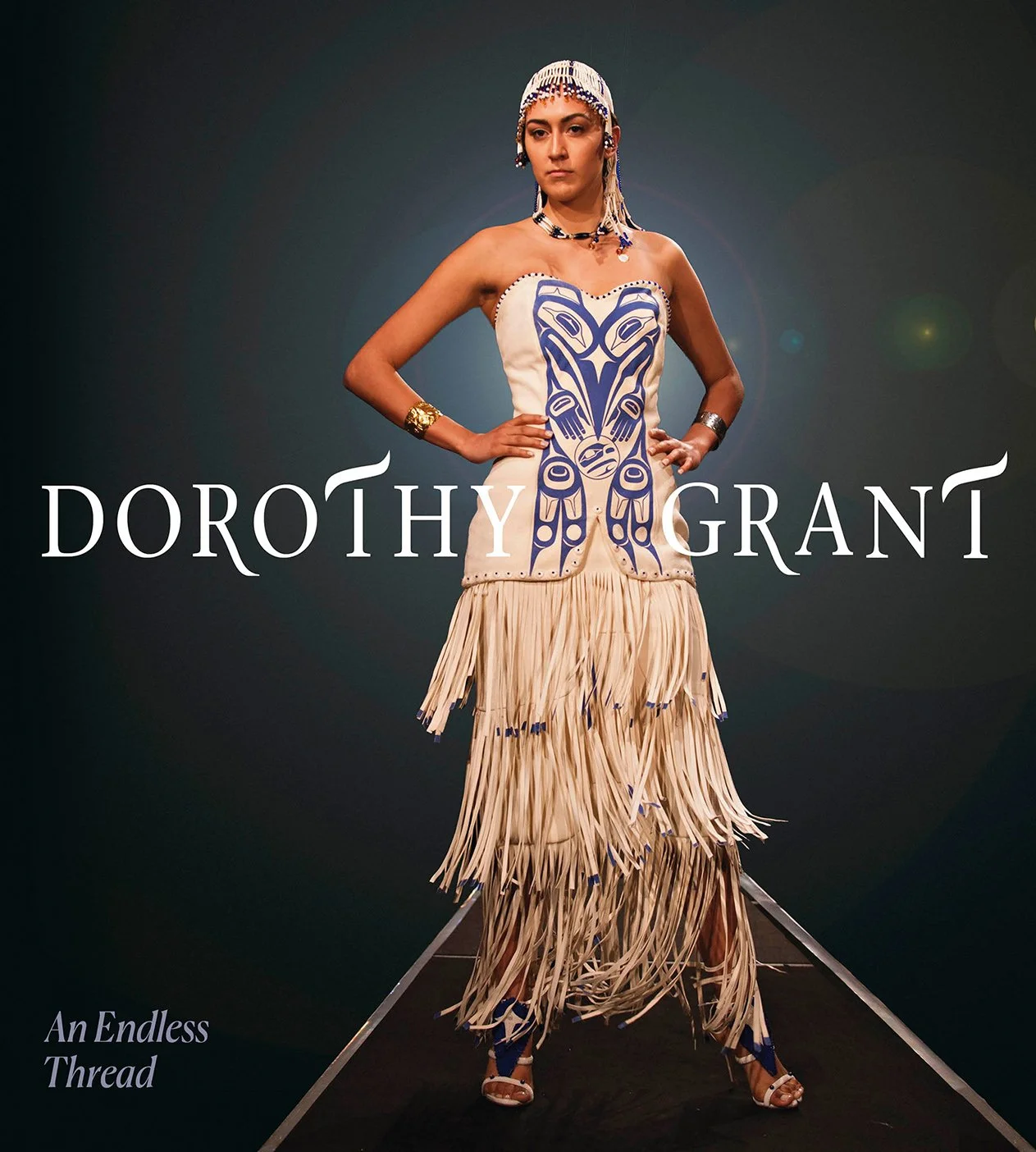

Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread traces four decades of a Haida haute couture trailblazer

Appearing at Vancouver Writers Fest, the designer talks about a 40-year career that set the stage for today’s explosion of Indigenous fashion

Some of Dorothy Grant’s iconic looks from the new book Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread. Photos by Farah Nosh

The book launch for Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread takes place October 26 from 1 pm to 3 pm at the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art. Vancouver Writers Fest presents Art Speaks: Dana Claxton and Dorothy Grant on October 27 at 5 pm at the Waterfront Theatre. Dorothy Grant: Raven Comes Full Circle continues at the Haida Gwaii Museum at Kay Llnagaay until December 21

THE RED-AND-BLACK formline-and-button Eagle Bolero. The flowy Feastwear Raven cape. The fringed white-deerskin wedding dress. And the distinctive, Haida-art-emblazoned power suits that clothed a generation of Canadian women leaders.

They’re all here in the new book Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread, B.C. fashion designer Dorothy Grant’s most iconic creations from her 40-year career, released this month by Figure 1 Publishing. But gathering all the looks for the fashion shoots in this monumental, hardcover retrospective—17 years in the making—was no easy task. That’s because Grant’s designs were, as she puts it, “scattered all over the world”—a testament to the vast reach of her Haida-design-emblazoned work.

“So from there, I just started collecting as much of my work as I could,” the pioneering artist behind the famed Feastwear line tells Stir in a phone interview. “And then people started gifting things back to me—major pieces. And so this collection formed that spanned my whole career as a designer. From that, we formed this exhibition up in Haida Gwaii called Raven Comes Full Circle. It’s kind of like the book became the catalogue for the exhibit,” she says, referring to the show that continues in the Haida Gwaii Museum at Kay Llnagaay until December 21.

Eight fashion photo shoots later, with many of the new images set amid the nature of Haida Gwaii, Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread tracks the remarkable career of someone who dressed celebrities and politicians, and sold her Haida haute couture from Paris to Tokyo—decades before there was an Indigenous Fashion Week or Indigenous fashion spreads in Vogue. The book includes essays by Haida repatriation specialist and museologist Sdahl Ḵ’awaas Lucy Bell, curator India Rael Young, and Haida curator and artist Kwiaahwah Jones. Grant will talk about the publication—part look-book, part memoir, and part illustrated history—at the Vancouver Writers Fest on October 27 at the Waterfront Theatre in a conversation with visual artist Dana Claxton (who’s just released Curve!: Women Carvers on the Northwest Coast). A day earlier, the book launch for Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread happens October 26 at the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art from 1 to 3 pm.

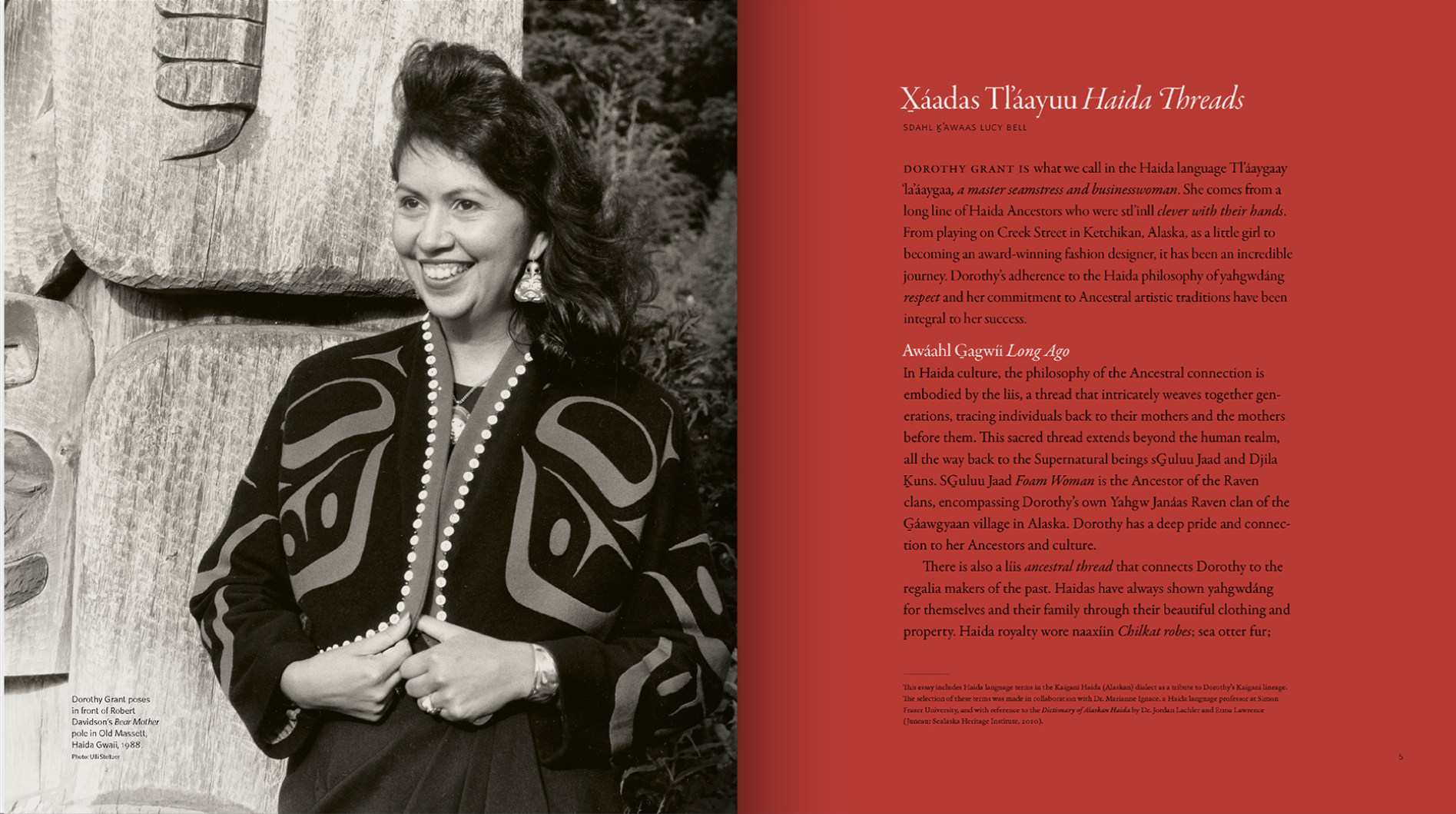

The book traces Grant’s inspiration back to its beginnings. Grant, who comes from the Yahgw Janáas clan of the Kaigani Haida in Alaska, says she had not grown up around much art-making. But by the early 1980s, she was creating intricate button blankets and spruce-root weavings for use in ceremony.

“I was young when I had learned how to sew from patterns and to use a sewing machine, and I was really, really passionate about it, even as a young girl,” she adds. “So making button blankets just seemed to become natural to me, and I was quite self-taught: I asked elders about what they do and how they do it, and so I leaned into that.”

Gorgeous images of Grant’s Two-Fin Killer Whale Button Robe, made in 1981, show her early talent: her first ceremonial dance blanket, all hand cut and sewn, features her round family crest in black and red, every line embellished with uncountable pearlized buttons.

Grant was also learning old songs and dances as part of the resurgence of Haida culture that was happening in a time when artists would often gather and share ideas. “It was bringing up ancestral memories—that’s what it felt like,” Grant says. “It was already in my DNA to feel this, to do this, and to, you know, push it forward.”

It was amid this artistically fertile era that she had a fateful conversation with revered Haida visual artist Bill Reid. She remembers it like it was yesterday.

“He was sitting at the kitchen table, and he was drawing a sketch of a big frog design, and he just started talking about how the art form needs to evolve into other mediums,” Grant recalls. “And that’s what a lot of the artists were feeling at the time—that we can’t just keep on doing masks and totems. It needs to evolve into something a bit more contemporary if we’re going to expand the art. And Bill said, ‘Well, somebody better do fashion.’ And I just took that as a seed, and I just kind of let it gel and gel, and I thought, ‘I can do this.’” Part of the motivation, she explains, was to protect Haida formline before it got into the hands of others who would not respect its traditions.

Grant, of course, would have a long tradition to draw on for her contemporary designs: as she’s quoted in the book as saying, “Our people have been in fashion design for millennia.” Intricate Haida garments long communicated knowledge and beliefs, including lineage, history, and the reverence for the natural and spiritual—traditions that carried forward despite centuries of colonization and potlatch bans.

From the beginning of her career, Grant has drawn deeply on yahgwdáng, an empowering Haida philosophy of respect for self, others, and those who went before you.

Set on her new mission to merge Haida traditions with contemporary style, Grant attended Vancouver’s Helen Lefeaux School of Fashion Design in 1987. In 1989, she launched the first collection for her line Feastwear—a seminal compilation of modern silhouettes hand-appliquéd with Northwest Coast formline. It included her iconic Eagle Bolero and a Full Circle Skirt, and instantly established her as a fashion force. It was a time, she reflects, when no other Indigenous designers were launching and branding themselves on such a large scale.

“For that fashion show in 1989, I had done everything properly—I hired a publicist and a stylist, and all the things that it takes to really make a fashion statement,” she says. “And there was a lot involved in that; I really stretched myself, but I knew that it had to have that impact for people to take notice.”

The book talks about the inner struggle she had, at first, in taking Haida designs beyond regalia and out into the wider world where they’d be worn by non-Indigenous people.

Dorothy Grant in a spread in Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread.

“The way that I view that is, when Bill Reid said, ‘You’re not selling a ceremony, you’re selling artwork,’ it just made me want to perfect my craft more, because I would be selling to the public,” she explains. “For me, I wanted it to be parallel to art, fine art, and that’s what drove me.”

In 1994, Grant opened her first boutique in the Sinclair Centre, a spot that included longhouse beams carved by Don Yeomans. From there her looks became iconic—particularly her power suits, worn by politicians, lawyers, and Indigenous elders across the country. In the book, you’ll see an array of them: the sleek black one with the scarlet handcut eagle shawl collar, or the black pinstripe suit with the wool and silk-satin-embroidery hummingbird design on its pointy collar.

Her clients have included The Revenant actor Duane Howard, Governor-General Mary Simon, and author and broadcaster David Suzuki. In the new book, you’ll also see an image of Canada’s first female prime minister, Kim Campbell, with her beloved red-and-black Feastwear cape taking a prominent spot in her official portrait, painted by David Goatley, on Parliament Hill.

“The garments that I focused on needed to be a classic shape, and they needed to fit a lot of different body types,” Grant says. “And that’s kind of how I approach design: what is practical for the wearer? I like the classics. I like things that will last in your closets for more than 20 years. Looking at it from the point of view of the wearer, if they’re going to invest in me and in my work, what does that look like? It’s the quality of the fabric—all my fabrics were natural fibres—and the cut work of the artwork had to be exacting. And the stitching: the inside had to be just as beautiful as the outside.”

Amid the milestones mentioned in the book was when Indigenous fashion finally took to the official runways of New York Fashion Week in 2009, Grant’s works sharing a high-profile show with Patricia Michaels and Virgil Ortiz. Her fashion labels have grown to include Dorothy Grant Gold and Red Raven by Dorothy Grant.

Today, a new generation of Indigenous designers, here and across North America, are filling catwalks. And Grant can take some credit for that. In the new book’s forward, the Haida Gwaii Museum’s Taa.uu ‘Yuwaans Nika Collison aptly calls Grant “the matriarch of Indigenous fashion”.

But it was not just the fashion world where Grant broke new ground: As Rael Young writes in Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread, “Grant broke through two glass ceilings simultaneously. Her fashions garnered the same art world acclaim as the sculptures, installations, paintings, and prints created by the men in her arts circle.” Look no further than the fact her garments can be found in museums and galleries around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Seattle Art Museum, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. In that way, Dorothy Grant: An Endless Thread works as much as a fine-art coffee-table book as an ode to couture.

Looking at her creations all finally gathered in one place, in both the book and the museum exhibition devoted to her tireless practice, Grant says she was in awe.

“It felt like I had come full circle. I had felt like all of those memories were flooding in on me,” she reflects. “I felt like all those people that had bought my garments before were behind me. I felt like the ancestors were behind me. I felt very secure, and I felt elation—a feeling of pride.” ![]()

Installation view of the exhibit at Haida Gwaii Museum at Kay Llnagaay.