Jack Shadbolt: In His Words paints a picture of a man who longed to be understood

Local arts critic and friend of the late artist, Susan Mertens, assembled the memoir from the painter’s journals, letters, talks, writings, and poetry

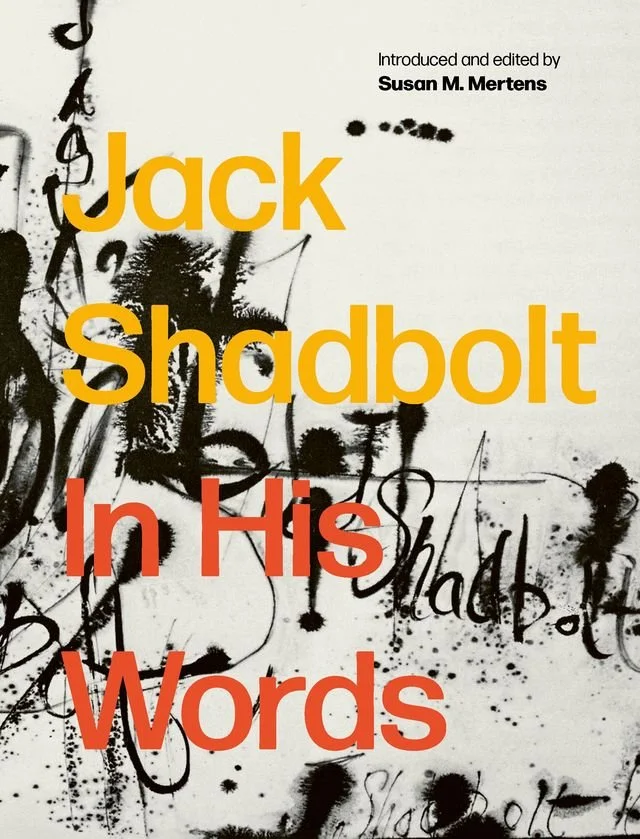

Jack Shadbolt. Photo via Figure 1 Publishing

Figure 1 Publishing presents You Don’t Know Jack (Shadbolt), an art talk with Susan Mertens, on November 14 at Shadbolt Centre for the Arts’ SCA Studio 103 at 7 pm

VANCOUVER ARTS CRITIC Susan Mertens had a 25-year-long friendship with iconic B.C. artist Jack Shadbolt. Having lived from 1909 to 1998, he was one of the country’s most prolific painters, profoundly influenced by West Coast landscapes. Now, Mertens has crafted an imagined memoir of his. Jack Shadbolt: In His Words pulls material from his self-confessional journals, letters, talks, writings, and poetry. What comes through are the thoughts of a man who wanted to belong and be understood.

In an interview with Stir, Mertens describes how she first encountered Shadbolt. She had just moved to Vancouver from Ontario, and the art critic at the Vancouver Sun was having health problems. Mertens got tapped to review a show of his without much of an opportunity to prep—this being the days before Google. “Besides, Jack was fresh; each show was another aspect of his curiosity, so you couldn’t rely on anything that had been written earlier,” Mertens says. “I found the works really puzzling and have since worked out why. It was a very strange show. It was in 1975, and he’d taken works from 1962 out of storage because they hadn’t worked and had had another go at them, so it was sort of a dog’s breakfast, and I was trying desperately to make sense of it. These works seemed to come from a very complicated person, and over the years I kept up on what he was doing. I didn’t write about him very much but I did socialize with him informally. We discovered we had this common ground and it was about the physical response to art. For me, it was as a viewer responding to the finished products; we would have these tense talks in the corner at somebody’s cocktail party about colour perception.”

Susan Mertens. Photo by Max Wyman

Here’s how Mertens describes Shadbolt’s work in the book: “The paintings he left us are, at their best, works of great psychic force—not conventionally beautiful, but offering an arresting, seductive, unsettling encounter. They are designed to have optimum visual impact: large-scale, eye-catching shouts of bright, rich, often acid colours; muscular, rooted constructions of forms tugging to be free of the canvas. Often produced in protracted series or multi-panelled formats, they increasingly gathered the inchoate and the highly composed into fleeting embraces, worlds momentarily conjured, an intake of breath before an expulsion. They are potent, vital, restless, intense, like their maker, who manipulated his materials until surfaces flare and underlayers smolder with poetry.”

Shadbolt needed to be making something from as far back as he can remember. He writes, “No other thing or process gives me the deep satisfaction of release that painting does. I suppose it’s like sex when you’re an adolescent. All you can dream about is the naked act, the lust—but even then it’s intermingled with some sort of romantic longing for ideal fulfillment in some atavistic way. You can’t really say how you get that way. You are that way. So when I paint it is because I need to paint. Which does not make me an artist, of course, but which guarantees authenticity. Perhaps that is why my art is not urgent or doctrinaire. It is too natural for me to want to intellectualize it by manifesto.”

The book features excerpts of letters Shadbolt wrote to school friends like John A. “Mac” Macdonald, among others, some written during his first teaching posts in Duncan and Vancouver. In one, he writes, “Drawing constantly is the only way to learn how to draw. Not that I have done so, you understand, but that I have improved tremendously—that I have begun to see a dim possibility ahead. And, too, that I have begun to realize what a vast subject art is—a tremendous unexplored land of promise and disappointment, of endless striving for rare and fleeting moments of pure joy.”

There are journal entries on what it was like to meet Emily Carr and Fred Varley; about his first time away from home, when he travelled to Chicago World’s Fair in 1933; and about his army service. He writes about his development as an artist, giving readers a greater understanding of the man behind such masterpieces as Inheritors, Tiger Hill, and Primavera. In an undated journal entry, Shadbolt argues there is truly an advantage in age. “With the trusted friends we have come to know and love we can argue, opt in or opt out of discussion with no questions asked and we have times together of true, unmitigated laughter. We laugh out our ruefulness, but we believe in one another’s search for meaning and respect one another’s necessary ways of coping. And we each know inwardly that we are all vulnerable enough to need each other’s support, each in his own private areas of insecurity.”

Mertens describes Shadbolt as a restless soul. “He had this energy and this restlessness to his paintings, I think. The very best ones—they look like something has just blown up or is just about to blow up or implode. There isn’t a restfulness. There’s this energy that’s either constrained or just about to go. I find that extremely attractive, even though it’s not an easy beauty. It’s kind of a jagged beauty, and a lot of people find his work difficult for that reason, even though he painted things like butterflies and owls. He had a wonderful sense of humour. He had a really heightened sense of the ironies of life, of being human.

“He had this terrific energy,” Mertens adds. “He had stamina and he had this work ethic that came out of being raised by a working class immigrant family. He was a toddler when he was brought from England to Victoria. We’d meet at an event and after 45 minutes we’re still in deep conversation, and I’d say ‘Jack, I have to lean against the wall or sit down!’ He had this ability to focus and the intensity… I think that combination is what made him so prolific. He had this real division in his personality. He had these painting bouts, as he called them, or campaigns or bouts, and he would go for days, hours, and he’d just fly, and he loved pushing himself to extremes within that. But then he would also crash and have these periods where he couldn’t work; he called them black periods. I think they probably were depressions, and he would be so frustrated and it was because the painting was the only thing that dealt with the stresses inside himself….It was the teeter-totter situation. He was really comfortable and happy, but he was also cranky and all the rest of it.” ![]()